Caitlin Clark, Gene Hackman, and Hope in Hoosier Land

Photo by Todd Lazarski

The Fever are going to win this game.

Caitlin Clark sits, jeans and t-shirted, injured but swaggily assured in her new role as de facto assistant, consigliere, team bulldog and referee-cajoler. With every whistle she is up, goading, clapping, mugging, almost “hold me back”-ing, intensifying a mounting comeback that resounds like a sports movie, when the popcorn has gone cool and the replays are slow and the strings might start to swell. The team has shrugged off a sluggish start against the Dallas Wings, one reflective of a humid Tuesday night in downtown Indianapolis, sleepy and slow and suggestive of the “Nap Town” nickname, the kind of evening where it’s hard to leave the hotel pool. Yet we’ve arrived for the moment, that time of fandom where you can defiantly deride the analytics, the math dorks, when you know: momentum is real. And magic, it is not only possible, but imminent.

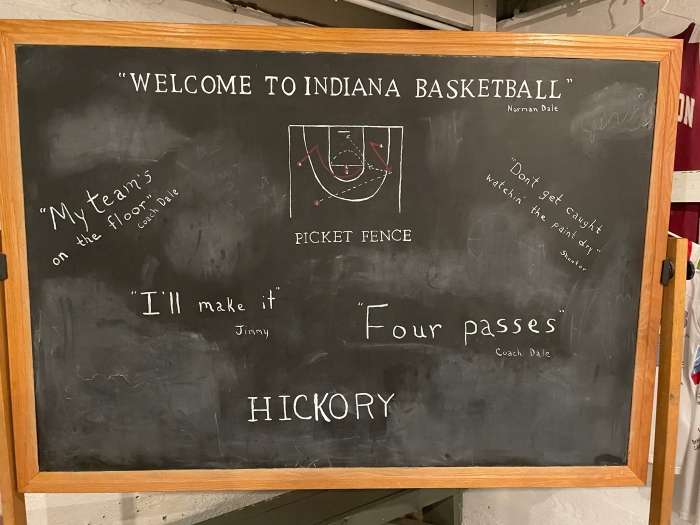

I’ve driven through Indiana, through the random rolling slowdowns and the Google maps indicating accidents you never see, the trucks and the construction, to end up here, in the nosebleeds of a nearly sold-out Gainbridge Fieldhouse, midweek in mid-summer, about to witness a real-life Hoosiers ending. A painstaking recreation has been canvassed for our arrival: after willing themselves back to life, from a deficit of 17 in the 4th quarter, the home team is down one, with the ball, huddling up in a timeout with 1.7 seconds left. Coach Stephanie White seems ready to draw up the Picket Fence, clearly, obviously, for mine and the crowd’s sheer cinematic enjoyment. The tall boy of Dragonfly IPA in my sweaty palm has been nearly forgotten in the commotion. The matching-hat elderly couple in front of me have been hanging, commenting on every possession. Now the husband stands in anticipation, moves two rows back to be alone with his feelings, his waiting-room anxiety.

The Fever are definitely going to win this game.

Indiana is the middle finger of the South, thrust into the center of the Midwest, according to Professor Lanier Holt. Favorite local son Kurt Vonnegut described the city as “the Indianapolis 500 and then 364 days of miniature golf.” I’ve heard the state called “Mississippi with corn.”

At the same time, it is easy to feel curious not about the city’s reputation, but by its complete lack of reputation. It is not befuddling, there is simply no fuddlement, one way or another, that seems to ever point the way of this massive burg of some 900,000. I’ve lived in Milwaukee, a mere 4-ish hours from Indianapolis, for over 20 years. In this time, I have never heard anyone say that they enjoy the city. I’ve never heard anyone say that they hate the city. I’ve never even heard of a person that has been to the city. The state itself seems ubiquitously disdained, scoffed at, but that seems to be mostly due to traffic and politics — understandable.

But what is Indiana? Is it Michel Jackson and Florence Henderson and Kurt Vonnegut and James Dean and Wes Montgomery and David Letterman and Hoagy Carmichael and Larry Bird and Oscar Robertson and Cole Porter and Woody from Cheers? Is it “Back Home Again in Indiana”? Is it Tyrese Halliburton’s corny but undeniable anti-heroics, that jittery Andrew Nembhard change of pace, the motoring pain-in-the-ass-ness of T.J. McConnell? Is it that looming 10-story Reggie Miller mural you can’t escape in downtown? Is it a big race and some Rudy and a whole lot of Hoosier lore? What even is a Hoosier?

Or is the state a place defined by the likes of Mike Pence? It is, at the very least, unfortunately, the site of the northernmost lynching ever recorded, from when Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith were taken from their jail cells in the town of Marion, in 1930. It was also, somehow, as likely no history teacher has ever been able to adequately explain, anti-slavery in its first constitution of 1816, and still explicitly forbade African Americans from settling in the constitution of 1851. Here, too, the KKK has flourished with a chilling malignancy: estimates hold that one third of the white male population were due-paying members of the Klan in the 1920’s.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-