The feds' plan to protect the Internet’s oceanic backbone from typhoons and cyberattacks

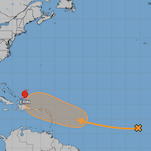

On July 9, 2015 a typhoon ripped through the Pacific Ocean, causing severe damage to an undersea cable that carried Internet to the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory and popular vacation destination. The damage left tens of thousands of Pacific Islanders and tourists unable to use credit cards, withdraw money, or make 911 calls for nearly a month.

The islands “lie precariously at the end of a single cable” and are particularly at risk of attack due to their close proximity to Guam, “the centerpiece of American military power in the Pacific,” wrote the Mariana Islands’ attorney general in a comment to the Federal Communications Commission.

The FCC, the agency tasked with overseeing America’s underwater cables, wasn’t alerted of the outage. According to Chairman Wheeler, the U.S. agency in charge of the internet had to figure out what happened by piecing together press reports and scrambling to make calls.

Ninety-five percent of global phone calls and Internet activity worldwide are transported by a vast, yet concentrated network of over 550,000 miles of submarine cables that string the continents together. Without these fiber optic lines the global economy would come to a screeching halt.

“They are responsible for $10 trillion worth of transactional value every day,” said FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel in a statement. “It is greater than the combined domestic product of Japan, Germany, and Australia. It is a big deal.”

The undersea cables that form the backbone of the internet as we know it are operated by a handful of telecoms with no government oversight. Right now, if an outage happens, the cable operators are asked to voluntarily report it, but that’s about to change.

On Tuesday, the Federal Communications Commission Chairman announced new rules for reporting outages in submarine fiber lines, not only to alert the government of critical damage caused by typhoons, underwater earthquakes, and piercing anchors dropped from fishing ships, but also sabotage and cyberwar.

The FCC is right to be concerned. The fiber-optic lines that pull all our data and cash across the planet with beams of light under the sea are vulnerable, each measuring less than two inches wide—about the size of a garden hose.

Earlier this year the FCC says, a lighting storm in Florida disabled the terminal center of a major undersea cable that connects multiple locations in the Caribbean to the U.S., knocking out the Internet and 911 service to the Cayman Islands. But AT&T, the telecom responsible for the terminal, didn’t notify the FCC and denies the outage even happened, despite an announcement from the local telecom authority that says otherwise. The FCC says it needs to be notified in order to take action if there’s been a disruptive outage, which can take days, especially if a ship has to travel far out to sea.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-